Where We Work

Our work takes place on the ancestral homelands of the Western Abenaki people. We honor and celebrate their traditional and ongoing relationships with these lands. We remember that this land is unceded and recognize the enduring injustices rooted in colonialism and the systemic oppression faced by Indigenous peoples. With humility and gratitude, we are committed to sustaining meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples; to sharing these lands as a place to gather, learn, and thrive; to exploring a deep sense of belonging to the universe; and to celebrating the natural world as the primary place of the sacred.

Vermont’s Center-West Ecoregion

Stroll across the village green in Bristol, Vermont, and you’ll spot the stately Old High School building on the green’s northwest corner. That’s where Vermont Family Forests keeps its small, but buzzing main office.

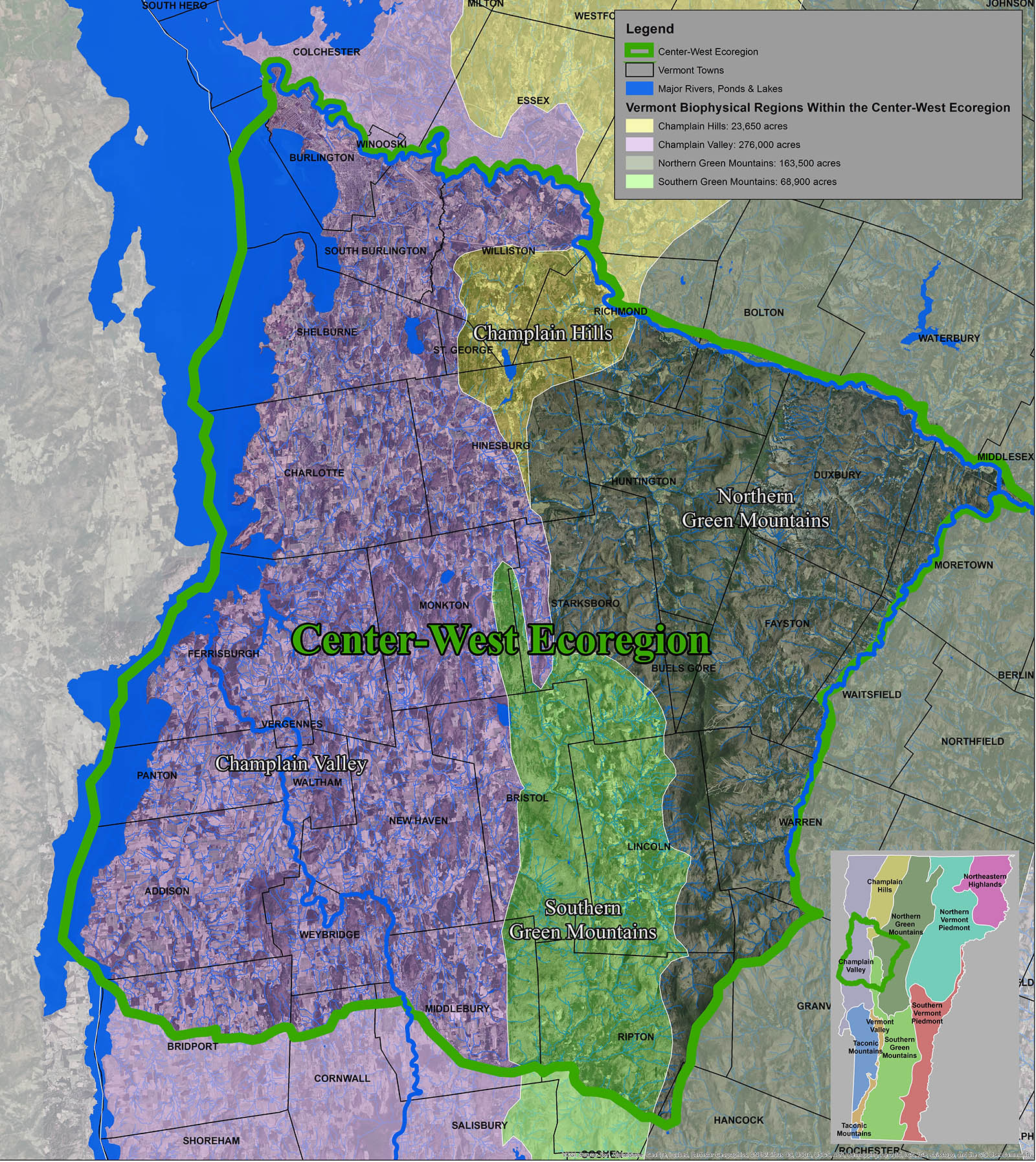

If you visit us there, you’ll see that one wall is given over to green binders–about 200 of them–one for each of the forest landowners we work with through our consulting conservation forestry. Together, these landowners hold about 20,000 acres located in 9 of Vermont’s 14 counties. The vast majority, however, lie close to our home base, in an area we call the Center-West Ecoregion. It’s a region roughly bounded to the west by Lake Champlain, to the north by the Winooski River, to the east by the Mad River watershed, and to the south by the Middlebury River and Route 125 (see map).

As you can see on the map, the ridge of Hogback Mountain–beautifully illuminated in the pale green shading of the Southern Green Mountain bioregion–juts north like a pinky finger, smack dab in the center of the Center-West Ecoregion. Bristol sits at the southern end of that wild ridge.

The Center-West Ecoregion encompasses the fields, forests, and waterways of home. It is where we in the 5-town area (Bristol, New Haven, Monkton, Starksboro, and Lincoln) work and play, where we ski, paddle, hike, pay taxes, raise families, shop, and gather with friends. It contains parts or all of 31 towns, and VFF landowners are located in 26 of these towns. Roughly 85% of the forestland owners VFF works with are located within the Center-West Ecoregion, holding a total of about 17,000 acres.

Why define the bounds of home? Gary Snyder wrote, “Find your place on the planet. Dig in, and take responsibility from there.” We’re digging in deep here, attending to the particulars this home landscape.

A science of land health needs, first of all, a base datum of normality, a picture of how healthy land maintains itself as an organism.

The story of the Anderson land is entwined with the two individuals who owned the land for more than 50 years. Lester and Monique Anderson purchased three separate farms in Lincoln in the early 1960s, all within a one-mile radius. For as long as they owned the land, they referred to each parcel by the name of the last farmers to own and work the land. Lester and Monique lived at the 134-acre Fred Pierce Place. Lester kept his office and Monique her extensive vegetable gardens and orchard on the second piece of land, the 112-acre Wells Farm. On the third parcel, Guthrie-Bancroft, Monique mowed the meadows each year, but otherwise the 470 acres were left to rewild.

Monique died at Wells Farm in 2013 at age 90. Lester died at the farm in 2015 at age 95. Lester and Monique bequeathed these lands to Vermont Family Forests, and in 2016 we had the honor and responsibility of assuming ownership of them.

Lester and Monique established “forever-wild” conservation easements for all three parcels, held by the Northeast Wilderness Trust. The conservation easements ensure that the land—with the exception of the homestead sites and existing meadows—is left alone to naturally rewild. These easements preclude all human activities in the forests other than scientific research and hunting.

The scientific research on these lands contributes to an on-going ecological monitoring project that Lester and Monique initiated in 1998, known as the Colby Hill Ecological Project. These conserved lands offer a rare opportunity to observe natural forest rewilding, providing what Aldo Leopold described as a “base datum of normality” for how healthy land maintains itself. This research effort will continue in perpetuity, and research reports are posted under our Resources tab.

Acknowledging the extinction of large predators–namely, mountain lions and wolves–from the forest ecosystem and the role hunters play in filling that niche, the easements permit hunting of non-predator species. VFF allows hunting of white-tailed deer and wild turkey by written permission on the 600 Guthrie Bancroft/Cold Brook lands. Each year 20-30 hunters request hunting permission.

Without application, principles and ideals have no bearing and no test.

In late 2017, we assumed ownership of 53.2 acres of wetlands and forest in Lincoln known to its former owners, Lynn and Willie Osborn, as Abraham’s Knees. Rising up the flanks of Mount Abraham, this land lies in the headwaters of the watersheds of home. Springs emerge from the mountainside here, flow in veins across the land and continue on to become part of Beaver Meadow Brook and, further on, the New Haven River and Lake Champlain.

We imagine this land as a place to practice wholistic, adaptive, forest-centered conservation. A place to explore mutually beneficial relationship with the forest through careful, contemplative, hands-on work with the land. A place to walk the talk of VFF’s organic forest conservation practices.

As such, Abraham’s Knees offers the perfect complement to the Andersons lands–a place to apply what we learn from naturally rewilding forests. A place to engage in mutually beneficial, participatory rewilding.

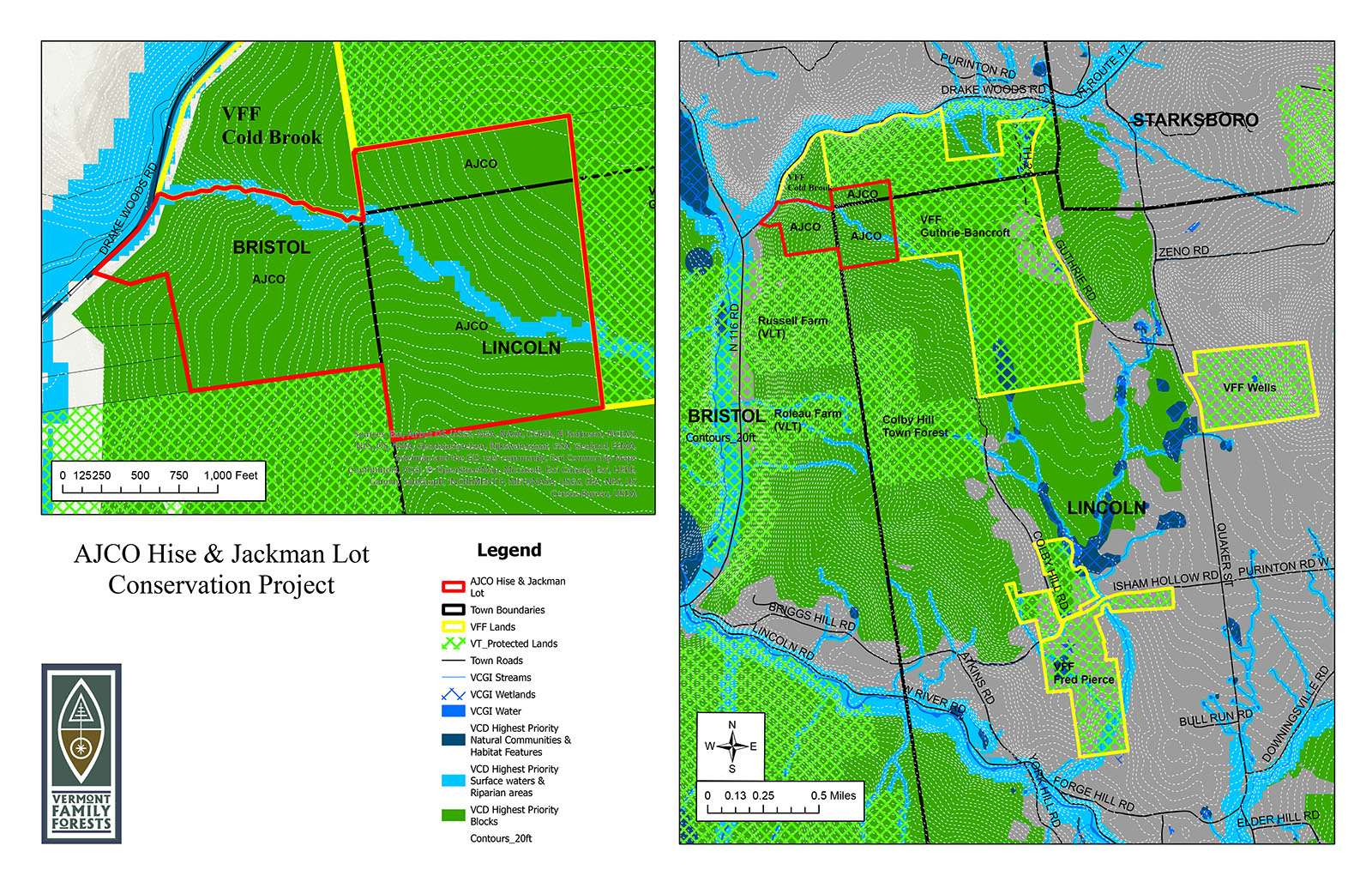

In 2020 and 2022, we purchased two pieces of land that together comprise 125.6 acres of land in Bristol and Lincoln. These lands abut the wildest portion of VFF’s Anderson lands—the 470-acre Guthrie-Bancroft parcel. They have been identified in Vermont Conservation Design as highest priority interior forest, and they are part of a wildlife habitat corridor between Hogback Mountain and the Green Mountains. Though these lands have steep access, they could have been subdivided and developed, with impacts on water, wildlife, and carbon storage. We called the land these two parcels protect “Cold Brook,” in honor of the beautiful stream that runs through them.

There’s a buzz these days about the idea of putting industrial forestry to work to advance old growth characteristics—to speed up forest rewilding and its associated ecological benefits. Our plan at Cold Brook is to encourage forest rewilding though non-industrial means. We’ll aim to practice ecological silviculture guided by the Vermont Family Forests Organic Forest Conservation Checklist—with access trails that are lines of grace; with appropriately scaled, light-on-the-land log forwarders rather than feller bunchers and grapple skidders; with uneven-aged management by area regulation rather than shelterwood cuts and clearcuts; with abundant biomass left onsite to restore the land and water quality. Throughout the process, we’ll monitor and document what we do and what we discover.

Just as the University of Vermont has an extension service that integrates and applies their latest research to land use practices, we’ll have our own CHEP Extension, where we apply what we’re learning about forest ecology on the adjacent Guthrie-Bancroft land, via the Colby Hill Ecological Project.