Sediment is the primary pollutant from roads on actively managed timberlands.

This summer, Vermont Family Forests teamed with the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps and local excavator Lucas Nezin to lend a healing hand on a piece of forestland we recently purchased, which had some significant erosion issues. Their work helps protect water quality, aquatic habitat, soil structure, and forest health.

The newly purchased 95.6-acre parcel borders a section of Route 17 known as Drake Woods Road, or Nine Bridges Road, named—as you might guess—for the number of times the road crosses Baldwin Creek in the steep-sided drainage. This new parcel abuts a 30-acre piece of land that VFF purchased in 2020. We’ve named these combined lands “Cold Brook,” in honor of the beautiful, clear, clean tributary stream that runs through them.

The Cold Brook land abuts VFF’s 460-acre Anderson Guthrie-Bancroft parcel. Together, these lands comprise most of the Cold Brook watershed. The waters of Cold Brook empty into Baldwin Creek on the north side of Route 17. Baldwin Creek, in turn, joins the New Haven River, which flows into Otter Creek, and on into Lake Champlain.

Baldwin Creek is topnotch brook trout habitat. To thrive, brook trout need cold, clear water and a gravelly, unsedimented creek bottom on which to lay their eggs. Since sediment is the primary pollutant from roads on actively managed timberlands, one of the most important tasks for forest landowners is to make sure their management activities don’t have off-site impacts on aquatic wildlife habitat.

Our aim is to keep Cold Brook running clear and clean. The 95.6-acre parcel came to us with a recently created logging road. About a third of a mile of it climbs grades of about 35% and was clearly showing erosion. Without some major work, it was destined to perpetually suck nutrients and moisture from the forest and send sediment into Cold Brook.

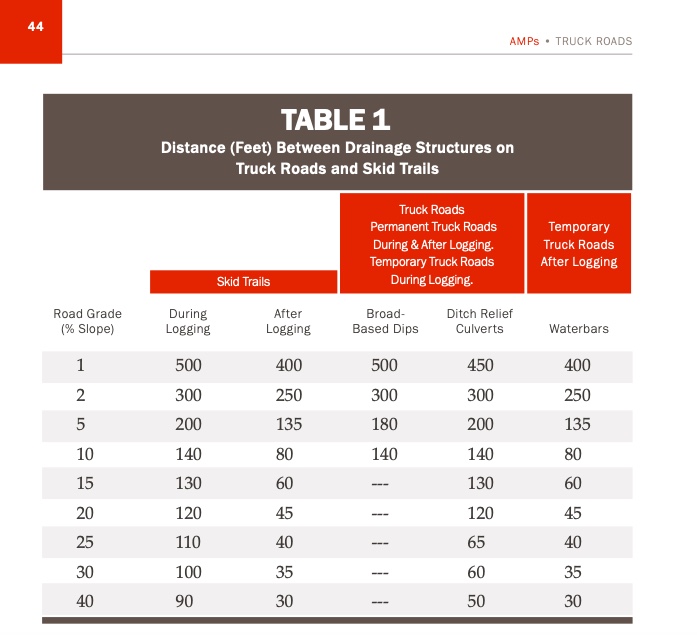

To comply with the Vermont Acceptable Management Practices (AMPs), as required for any landowner participating in Vermont’s Current Use program, forest access roads must have effective erosion control, like broad based dips, culverts, and/or water bars.

The AMPs clearly describe the number of erosion control features needed, depending on the slope of the access road. As you might expect, the steeper the road, the more erosion control features you need. A 1,500-foot access road with a 5% grade needs 11 erosion control features to comply with the AMPs. At a 35% grade, that same length of road needs 47 erosion control features.

When we assessed the roads on the new parcel, we found that they needed a total of 134 waterbars. Excavating that many waterbars was beyond our budged for this year, so we opted to complete half of them now, focusing on the steepest road sections where erosion was most intense.

We opted for deep broad-based dips that could hold up to the increasingly powerful storm events that climate change is bringing to our region, These dips would both divert runoff back into the forest and block vehicle access. Our aim was to permanently close the road and to jumpstart the healing process through active rewilding.

We wanted to accomplish all this while minimizing cost and optimizing labor. We hired local excavator Lucas Nezin to construct the broad-based dips. Lucas’s equipment operator Andrew Cousino skillfully built 65 very deep, heavy-duty broad-based dips at a cost of $60 per dip.

With the broad-based dips in place, it was time to bring in hand tools and hand labor to protect and stabilize soils on the logging access road. After last year’s successful collaboration with the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps, we signed onto another week of VYCC work for this summer. The eight-member VYCC crew camped at VFF’s Anderson Wells Farm in July while they worked on the Cold Brook project. Starting at the top of the stretch of broad-based dips, they pulled logs and branches from the surrounding forest to cover the bare ground between dips. Laid along the land’s contours, this organic matter will slow the flow of rainfall, hold moisture and sediments, and shelter seed growth.The VYCC crew also rewilded a wide log landing at base of the access road along Route 17. We wanted to maintain a small parking area to accommodate a few cars, but rewild the rest of the log landing. The VYCC crew first cleaned litter from the site, then scattered annual winter rye and covered the seed and soil with straw. They then pulled logging debris and other downed wood onto the seeded area to hold down the straw and stabilize soils.

During an end-of-the-week site visit to see and celebrate their work, the VYCC crew members noted how good it felt to be part of a project focused not on peoples’ need, but on the health of the land. For us at VFF, one of the most inspiring aspects of this project was that every one of the workers on this project—from the excavator operator to the VYCC crew—was under the age of 25. Young people healing the land. That’s a mighty hopeful thing. Two weeks after the VYCC crew finished their work, the winter rye was up and growing fast, already at work holding and enriching the soil. Heartfelt thanks to all who lent a hand. We’re already looking forward to next summer’s collaboration on behalf of forest health.