Old logging roads and present-day phosphorus pollution

This past summer, Vermont Family Forests oversaw installation of erosion control structures on forest roads at the Seth Hill Waterworks, a parcel of land in Lincoln that’s owned by the Town of Bristol. We paid for this work with grant funds from the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation’s Clean Water Service Provider (CWSP) Program, locally administered by the Addison County Regional Planning Commission (ACRPC).

The purpose of the CWSP grant program is to reduce phosphorus inflow into Lake Champlain. Phosphorus is one of the lake’s primary pollutants, found in fertilizers, animal waste (cow, human, and otherwise), and soil sediments. Too much phosphorus pumps up aquatic plant growth in the lake, disrupting the lake’s ecological functions. As these abundant plants decompose, they use up dissolved oxygen, which stresses fish and other aquatic organisms.

Together with the Green Mountain National Forest lands that surround it on three sides, the 113-acre Seth Hill parcel comprises much of the headwaters of Downingsville Creek, which flows into the New Haven River and on into Lake Champlain. The land has been owned by the town of Bristol since 1905, and its abundant spring served as Bristol’s water supply for many decades, up until about 20 years ago. Due to the prolific streams that flow through it, the majority of the Seth Hill forest property is riparian habitat. This land has been heavily logged in the past and, except for the very steepest areas, is extensively roaded. The primary pollutant from logging and logging roads is sedimentation, and virtually all of the logging roads on Seth Hill lack adequate erosion control structures to slow, spread, and sink the flow of stormwater.

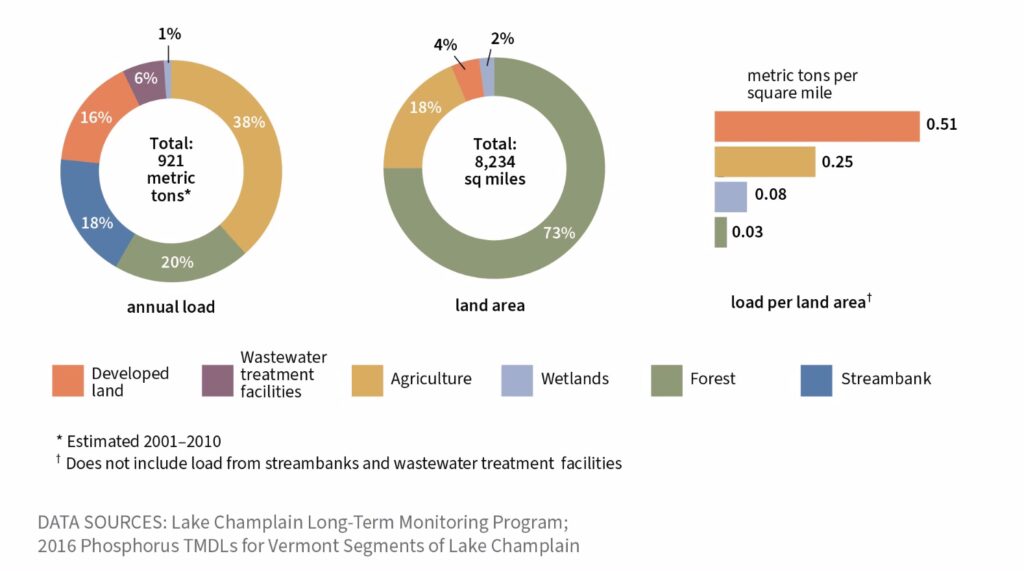

The Lake Champlain Long-Term Monitoring Program table below lists the lake’s main sources of phosphorus pollution. Farming leads the pollution pack, contributing 38% of the lake’s inflowing phosphorus pollution, though it accounts for just 18% of the state’s land cover. Forests contribute 20%, which by and large comes from eroding access roads. The last of the top three phosphorus sources is streambank erosion, at 18%.

Parsing these percentages is important, since it’s our sense that streambank erosion, though considered separately from forests as a phosphorus source in the table above, is intimately connected to what’s happening in upland forests, particularly within the access road network. More about that later.

Despite the significant contribution of forests to elevated phosphorus levels in Lake Champlain, our CWSP grant proposal was the first forest-based phosphorus reduction proposal that ACRPC received. Our sense is that that’s related, at least in part, to systemic issues within the Current Use program. In signing the signature page of their forest management plan for Current Use, landowners agree to manage their land in compliance with Acceptable Management Practices for Maintaining Water Quality on Logging Jobs in Vermont (AMPs) in order to control stream siltation and soil erosion.

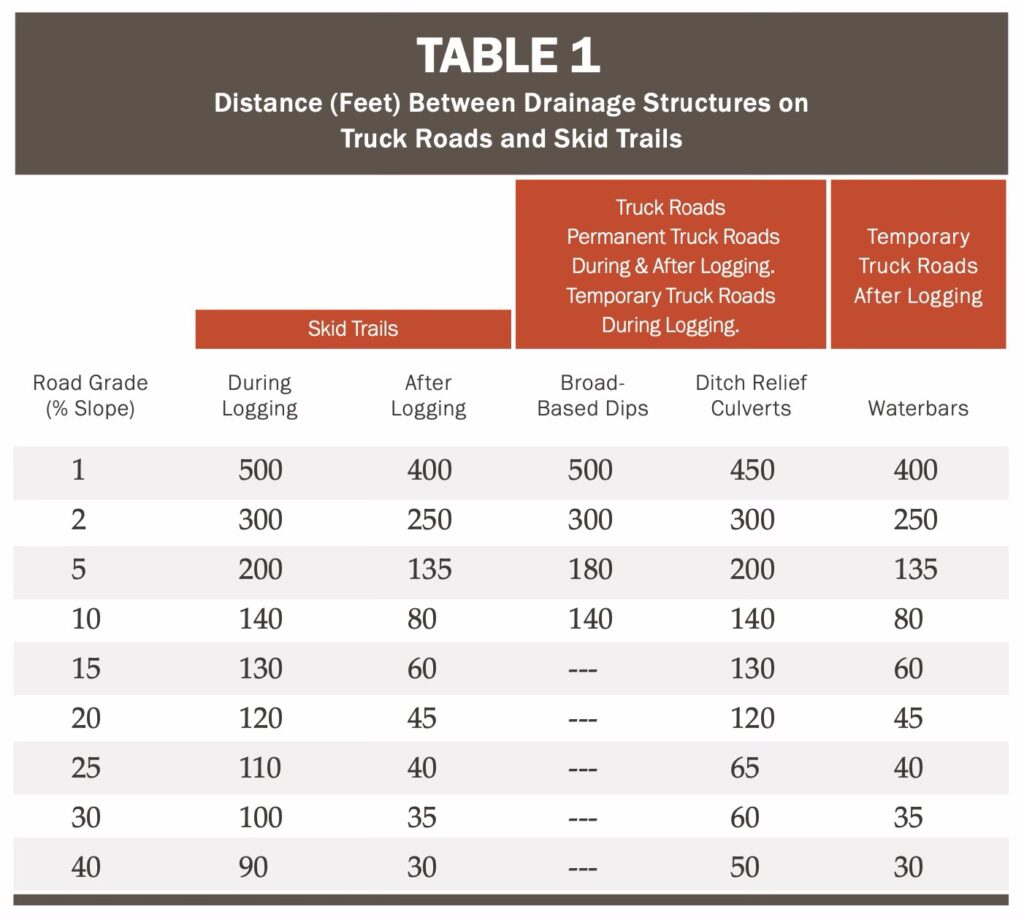

The simple fact is, that’s a rarity. Few forest parcels enrolled in Current Use have an access road network that fully complies with Table 1 of the AMPs. To avoid setting a precedent of providing grant funds to fix problems that landowners should be addressing as part of their obligation within the Current Use program, the Department of Environmental Conservation will only consider grant projects involving historic logging roads that remain a water quality concern today (as opposed to forest roads associated with recent logging work).

No problem for our proposal—all the truck roads and skid trails we were interested in restoring fit the historic category. In our initial proposal—based on the inventory work VFF executive director and conservation forester David Brynn did when updating the property’s Current Use forest conservation plan in 2023—we envisioned installing in the neighborhood of 100 erosion control structures. David’s inventory had included both the two main truck roads and the many residual steep skid trails.

These residual skid trails are deeply incised from past erosion. Although enough time has passed that they have grown over with herbaceous and woody plants and no longer actively erode, they still concentrate storm flow. This concentrated flow into Downingsville Creek contributes to elevated river levels and streambank erosion downstream. (Remember that 18% of phosphorus loading attributed to streambank erosion mentioned earlier?)

Excavating deep waterbars on these rewilded steep skid trails would create temporary soil disturbance, but we felt that the long-term hydrological benefits of slowing, spreading, and sinking storm flow on these incised dugways was well worth the short-term site disturbance. Over the past few years, we had constructed erosion control structures on similarly steep logging roads in Lincoln and Bristol with overwhelmingly positive results. A good excavator operator can work with surgical precision on such rewilded sites, minimizing soil disturbance while maximizing the benefits of redirecting storm flow back into the forest.

After being approved for grant funding, we flagged the proposed sites to receive erosion control structures. Roughly a third of the structures were earmarked for the two main truck roads, which are currently used by the local sugarer who leases the land for sugaring and by recreationists, who walk, bike, and ski here. The rest were flagged on the deeply incised old skid paths.

We then walked the proposed project area with representatives of the Agency of Natural Resources, who determined that the old skid roads were not eligible for project funding because they had rewilded to the point that they were considered in compliance with Vermont’s Acceptable Management Practices.

That made us scratch our heads. After bleeding soil from these steep skid paths for many years, resulting in deep dugways and stream siltation, Nature had slowly scabbed the wounds, in terms of active soil erosion. Roots and leaves of herbaceous plants now anchor the skid roads’ soil, and fallen leaves buffer the erosive impact of heavy rains. Because of this, they don’t fit into the state’s phosphorus-reduction calculations, even though these steep dugways continue to suck water out of the forest and contribute to river flashiness and streambank erosion downstream.

As a result, we focused our erosion control structure excavation on the two truck roads on the property, which met the phosphorus-reduction criteria. Chris Cram of Atkins Excavation constructed 35 erosion control structures of three different kinds, depending on the steepness of the road gradient. He excavated broad-based dips in road sections with grades of less than 10% grade. In road sections with grades of 10-12%, he reinforced the broad-based dips with 4-6” crushed rock to improve durability. In road sections with grades greater than 12%, Chris installed deep waterbars, which are needed to prevent blow-out during intense storm events. Immediately following construction of the 35 erosion control structures, we seeded bare mineral soil along the access roads with Vermont Conservation Mix.

With minimal maintenance, these erosion control structures should protect water quality in Downingsville Creek for many years to come. Since the structures divert water back into the forest, drenching rains can replenish forest groundwater and be taken up by the roots of sugar maples and all the other plant species in the forest. That’s good for the forest, and it happens to also be good for the sugar-maker. More groundwater, more sap—that’s the sweet taste of ecological restoration.

History reveals that soil depletion has precipitated the collapse of whole civilizations (see Dr. David Montgomery’s 2012 book, Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations). Current conventional forestry practices in Vermont continue to focus of stand structure, and even the latest ecological forestry tomes barely mention the forest access network and its pivotal role in conserving or depleting forest soils, on which the forest’s vegetative structure depends.

We will continue to explore the AMP interpretations that overlook the ecological impact of hydrological issues on rewilded historic logging roads-turned-dugways, and consequently limit access to funding to address those issues. There’s a significant opportunity to have positive impacts on Vermont hydrology and water quality if we put more emphasis on forestry that slows, spreads, and sinks peak storm flow. It’s an essential part of coping with the increasingly intense storms associated with climate change, and it’s front-and-center in our work at Vermont Family Forests.