By Sandra Murphy

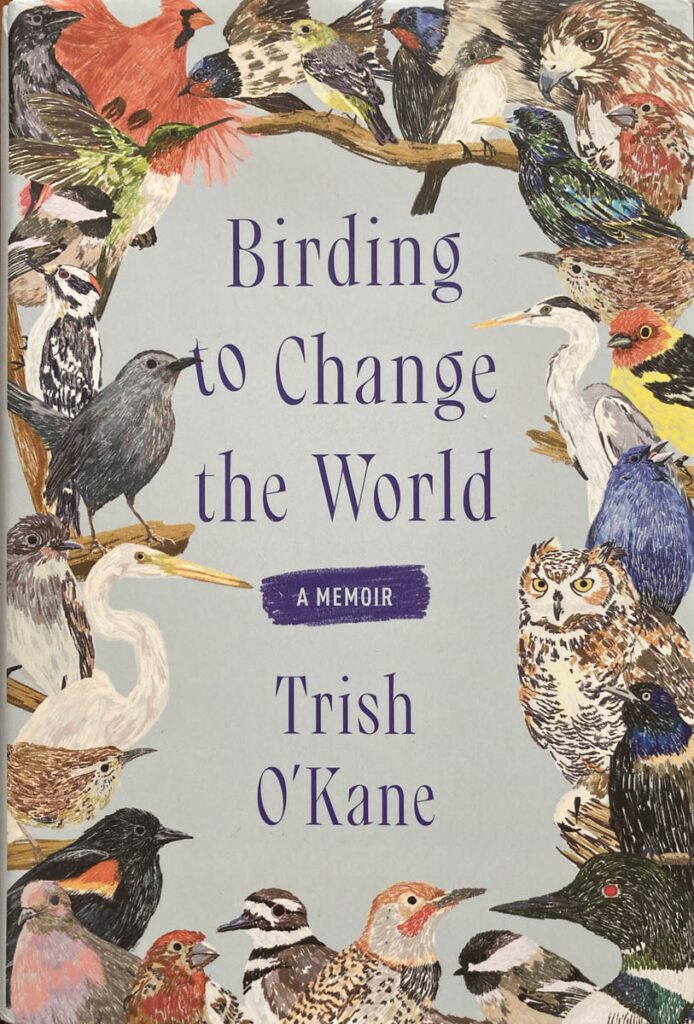

At Vermont Family Forests, each new year starts with a look back at the previous one, as we pull together our annual report. And each year, certain books rise to the surface as inspirations to the work we do. One literary highlight of 2024 was Birding to Change the World, by Trish O’Kane. Echoing the title of the service-learning program Trish leads at the University of Vermont, Birding to Change the World is a lifeline in the turbulent waters of our times, and it directly relates to what we’re up to at Vermont Family Forests.

I won’t take a deep dive into the book here (In a nutshell, read it! It’s a page-turner that’s inspiring, funny, hope-inducing, and beautifully written), but instead want to focus on its connections with forests and landowners and community, which are the heartbeat of what we think about and do.

The premise of Trish’s Birding to Change the World program at UVM, as I understand it, is simple: immerse college students from all walks of academic life in birds and birding, pair them with local elementary school kids for one-on-one birding outings in nearby nature, and transformative things will happen.

In a public radio interview in December, when asked why she spends time each day looking and listening for birds, Trish responded that it’s her medicine, and it’s the news. “I tell my students—the news is not just what’s in the media. There’s news out there every day. As soon as you open your window, you can hear it. What are the birds saying? Go and watch, go and learn.”

That message struck a deep chord. As ecologists Ted Mosquin and Stan Rowe articulated in A Manifesto for Earth (2004), meaningful ecological restoration requires a shift from human-centered to Earth-centered perspectives. Trish’s encouragement to regularly tune into the breaking news from the other-than-human community of life is one meaningful step in that direction.

Bird by bird. Does seeing a cardinal change the world? What about the rippling effects of lifetimes of bird awareness and love and care? “Drops of water turn a mill, singly none,” Pete Seeger sang. Together, drops become a stream, with the power to move mountains.

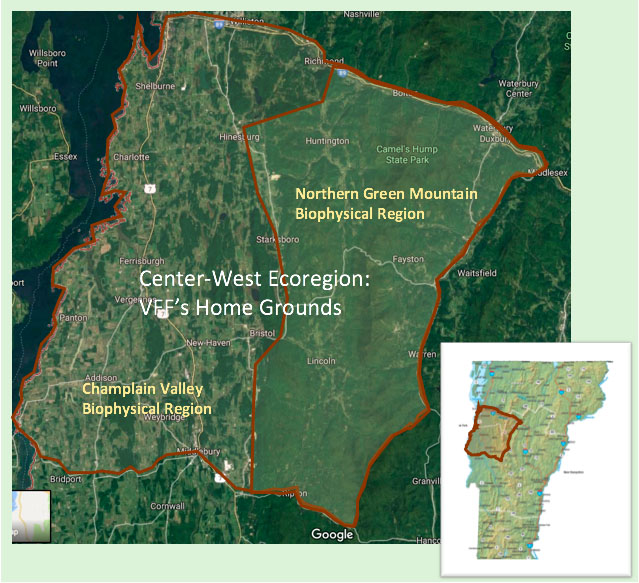

That flowing metaphor for Trish’s work has practical resonance at Vermont Family Forests, where we spend a lot of time thinking about the collective power of raindrops as concentrated stormwater flow and how to make effective changes that will help keep soil in forests and out of streams and rivers and Lake Champlain.

Here in Vermont, centuries of forest clearing, steep logging roads, and straight-up-the-slope skid paths have created a state-wide network of eroded channels that suck water and soil out of upland forests and into nearby streams and rivers, which rise quickly during storms—laden with sediment—and barrel downstream, scouring their banks and whatever else lies in their swollen path. As storms increase in intensity and frequency with climate change, so does the problem. How to effect meaningful change?

Waterbar by waterbar. On our own lands, where both historic and recently created logging roads were far too steep, we’ve installed at least 130 erosion control structures—from gentle broad-based dips to road-closing tank traps, depending on road grade—to slow, spread, and sink storm flow (See related stories, Big Storms and Forest Roads and VYCC Helps Heal a Steep Access Road). In 2024, we continued that process at the Seth Hill Waterworks in Lincoln—land owned by the Town of Bristol.

Does one waterbar make a difference in the big scheme of Vermont’s flood resiliency? What about a dozen waterbars on a hundred family forests in the Center-West Ecoregion, this place we call home? Across the state, there are more than 76,000 family forests covering 2.7 million acres—that’s a whole lot of erosion control, if we all step up to it.

Trish O’Kane’s book encourages us to tune into the news of the birds. Widening the lens, we can tune into the news of the forest community, alive with stories of bear-clawed beeches, fungus-stippled snags, and brook-trout-studded streams. A ragged furrow along a forest path might be telling a story of water running unfettered downhill for too long a stretch. But the good news is there’s soul-restoring work to be done to help. Build a waterbar—an appropriately sized, effective, long-lasting, soil-protecting waterbar. Or two. Or a dozen. But it all starts with one.