Tagging along with mammalogist Chris Gray when he’s monitoring small mammals for the Colby Hill Ecological Project means getting up early. The sun has yet to crest the Green Mountains when we meet at 6am on a dewy, fog-draped August morning at the entrance to Vermont Family Forests’ Guthrie-Bancroft land in Lincoln. Within minutes we’re striding through the rain-soaked field on our way to the first trapline.

It’s the last day of his second four-day field survey of the season, which means Chris will be gathering up the traps as he goes. Helping him with that cumbersome task is Carlos Amissah, a first-year Ph.D. student at the University of Vermont. After earning his master’s degree in wildlife management from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, Carlos is now working with UVM professors Nicholas Gotelli and Ellen Martinsen to research the interactions between ticks, host species, pathogens, and the environment and how these factors influence the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens. The research team is interested in collecting ear clip samples from wild-caught small mammals in Vermont to get a better idea of the possible reservoir hosts of these tick-borne pathogens.

To carry out that research, Carlos needs to learn the art of live-trapping and taking tissue samples from small mammals, which is why he has joined Chris for this 4-day field survey. For the past three nights, Chris and Carlos have stayed at VFF’s nearby Anderson Wells Farm, setting the traps in the evening and checking them first thing in the morning. Chris is one of several mammalogists who have carried out the annual monitoring of small mammals for the Colby Hill Ecological Project (CHEP) since 1998.

The 6am start time, Chris explains as we follow his flagged path through the forest to the first trap line, is necessary to limit the amount of time any trapped mammals spend in the traps. Spending too much time in a trap, especially if it’s wet and cool, can be lethal. Chris had tried to time this four-day trapping event to coincide with fair weather, but met with scattered rain showers during the four days of trapping.

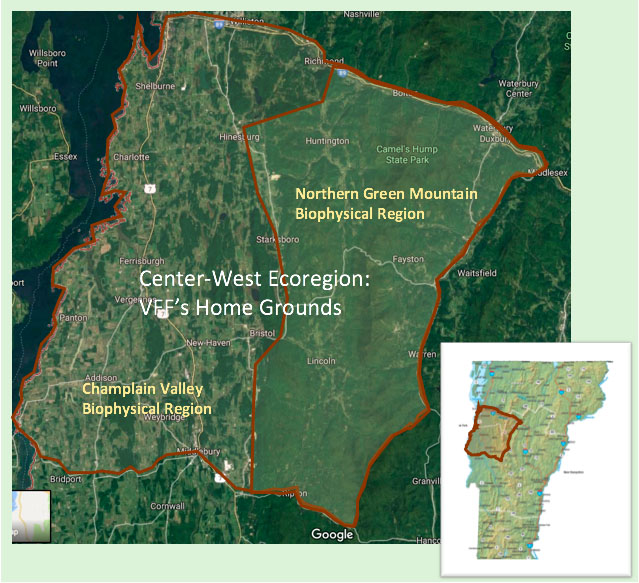

Rubber boots squelching in mud, we reach the first two Sherman traps along the trapline in Ecosystem (ES) 20, one of four designated small-mammal study sites within the 470-acre Guthrie-Bancroft parcel. ES20 is an early successional alder swamp/sedge meadow—a remnant open area from the days when much of the Guthrie Bancroft parcel was cleared for farming—that’s slowly returning to forest. Wet by nature, it’s particularly wet now, after many drenching summer storms.

Chris and Carlos have set a total of 70 Sherman traps and 9 pitfall traps along the two spurs of the trapline in ES20. We start at Station A18, the end of the trapline, and work our way back toward the beginning. The first 7 stations, each set with 2 Sherman traps, have no captures, foreshadowing a low collection rate for the day, likely related to the wet weather. At station A11, one of the traps is closed. The occupant—an American short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda)—is dead. Chris explains that their phenomenally high metabolic rate means they quickly succumb—especially if the night is cold and wet— if they can’t actively forage.

Carlos weighs the dead shrew (15g), then works with Chris to collect a small sample from the ear for study back in the UVM lab. He places the sample in a labeled tube, then tucks the shrew into the collection box for further study at UVM. Following a data protocol established when this long-term study began more than 20 years ago, they record information about the capture site—distance to nearest downed log, canopy cover, and so on.

As they work, Chris enthusiastically expounds on the coolness of shrews. Like moles, shrews have velvety fur that easily lays flat in any direction. That’s a great adaptation for below-ground living, where backing out of tight tunnels is part of everyday life. Contrast that, he says, with most other mammals, where fur orients in one direction (Imagine petting a golden retriever from tail to head—the fur resists the motion.).

At Station A6, one of the traps is closed, and Carlos gently shakes a lively Eastern meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) into a small plastic bag. Carlos weighs the bag (22g), then carefully grasps the vole by the scruff of the neck, so he and Chris can examine the animal more closely and take a small ear tissue sample with a punch tool.

Chris is intrigued by the fact that meadow voles live in this small island of relatively open habitat, which is now surrounded by hundreds of acres of mature forest. Did they migrate here though the forestland? Or is this vole perhaps part of a remnant population from past farming days?

A little further along, we reach a pitfall trapline that Chris has set to target species from the Sorex genus, commonly known as shrews, which aren’t enticed by the oat-baited Sherman traps. Nine small plastic cans are buried with their rims at ground level at intervals along a foot-high plastic drift fence. When small mammals encounter the fence, they follow along it as they look for a way through, and—Chris hopes—fall into a plastic can. Alas, that didn’t happen this time—the cans are empty when Carlos checks them.

At Station A1, we find the third and last mammal of the “A” trapline—another short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) that, like the first one, succumbed to the night’s cool, damp weather. Chris and Carlos carefully weigh the shrew (23g), collect an ear tissue sample, and tuck the shrew alongside the first for further study at UVM.

I part with Carlos and Chris at Station A1 and follow the flagged route back to my car as they head deeper into the forest to check the second ES20 trap line. Chris tells me later that they found another 3 mammals along that trapline. They also checked and retrieved traps at ES14, where they found and gathered data on 14 more mammals.

It’s always an immense privilege to accompany CHEP researchers during their fieldwork. Their passion, curiosity, rigorous attention to the scientific process, and love of the wildlife they study are a joy to behold. Thank you, Chris and Carlos, for your dedication to wildlife research and conservation.

You can take a look at all of our CHEP small mammal reports on the Vermont Family Forests website.