For more than 25 years, herpetologist Jim Andrews has monitored reptile and amphibian populations for Vermont Family Forests’ Colby Hill Ecological Project (CHEP). When Lester and Monique Anderson initiated this long-term ecological study in 1998, their intention was for this on-going research to help inform forest conservation efforts across the greater landscape. As an extension of Jim’s CHEP monitoring work on Vermont Family Forests lands in Lincoln and Bristol, VFF hired Jim and his monitoring team to assess amphibians and reptiles (collectively known as herptiles, or “herps”) at the 1,001-acre Lands of The Watershed Center, a community forest in Bristol and New Haven with which VFF has been closely connected since the two organizations came to be.

As keynote speaker at The Watershed Center’s 2024 Annual Meeting in May, Jim shared his research, focusing on the critical role The Lands of The Watershed Center play as habitat for several rare and threatened herptile species, and the critical role of the conservation easements in conserving that essential habitat. Though Jim’s captivating presentation wasn’t recorded, the text and images below capture much of its essence. (Photo above of Eastern ratsnake by Cindy Sprague).

Conserving Herps on the Lands of the Watershed Center

Adapted from Jim Andrews’ keynote address to The Watershed Center 2024 Annual Meeting.

Click on any of the images below to see enlarged view.

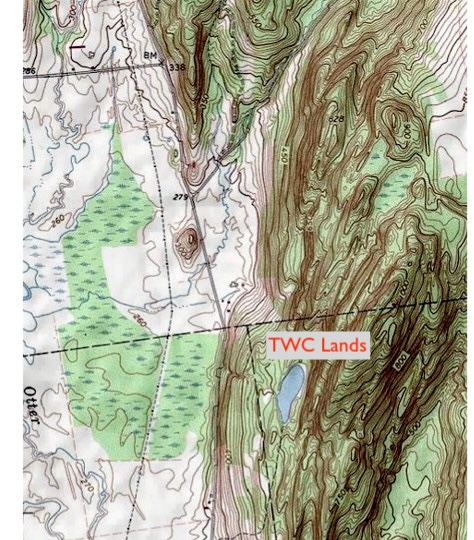

Community members love the Lands of The Watershed Center (TWC)–a beautiful, 1,001-acre conserved area in the northwest corner of Bristol and eastern edge of New Haven. It’s become a beloved place for people to recreate, unwind, and connect with nature. But recreation is just one of the conservation values of these lands. Across much of the TWC area, the land’s primary conservation purpose–as defined in the conservation easements that guide their management–is to protect critical habitat for wildlife. Jim Andrew’s recent presentation dove deep into the phenomenal biodiversity of this land and how the varied conservation easements in place on the land help protect that biodiversity and essential habitat.

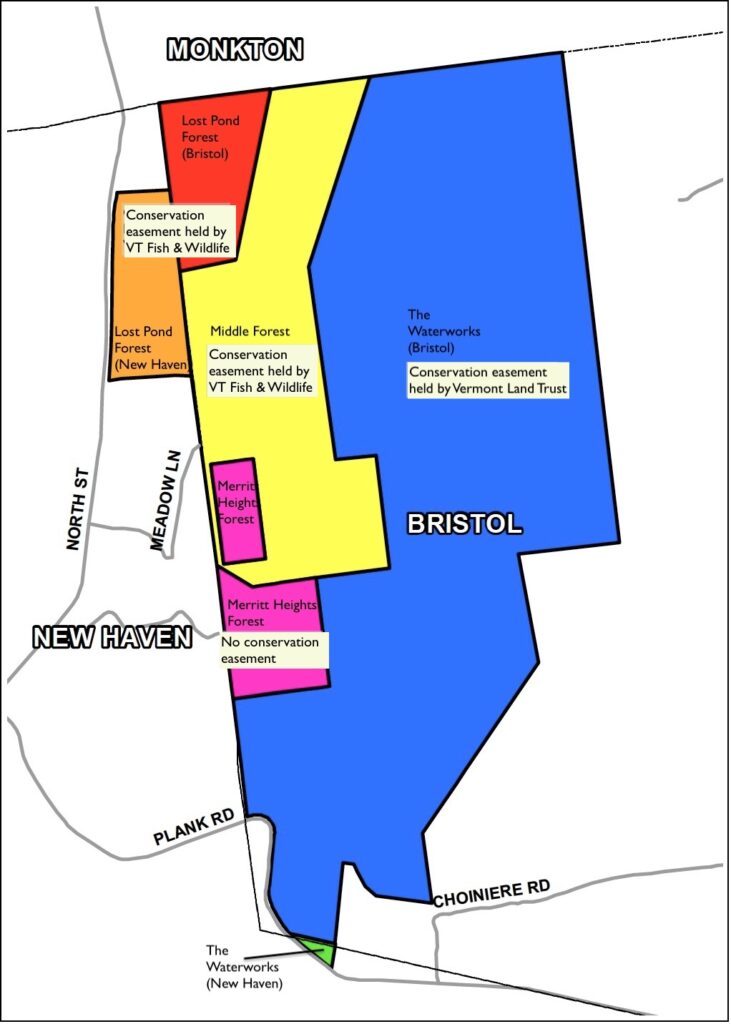

The Lands of the Watershed Center are comprised of four different, contiguous parcels, as you can see in the map, right. [See VFF’s recent blog, A Place for the Birds, for more details on these land acquisitions]. With the exception of the Merritt Heights parcel, all the parcels that make up the Lands of The Watershed Center(TWC) carry conservation easements held either by the Vermont Land Trust (VLT) or the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife (VTF&W).

Most land trusts create conservation easements that prevent development and maintain “open” land. But the primary goals of different conservation trusts differ and their easements differ as well.

The Vermont Land Trust easement on The Waterworks parcel—the original and largest portion of TWC lands—is fairly general in its language, though it specifically mentions conservation of wildlife habitat. Its stated purpose is:

“To conserve and maintain the protected property as a generally forested tract with its associated wildlife habitats, natural communities, non-commercial recreational opportunities and activities, and other natural resource and scenic values for the benefit of present and future generations.”

So in the case of The Waterworks parcel, habitat protection is one of several goals of the easement. In the case of the Lost Pond and Middle forest parcels, however, the conservation easements are quite different. Here, wildlife habitat protection is the top priority. These easements define their purpose this way:

“To conserve and protect biological diversity, important wildlife habitat and natural communities on the Protected Property and the ecological process that sustain these natural resource values as these values exist on the date of the easement and as they may evolve in the future.”

These easements specifically note that the primary purpose is to protect eastern ratsnakes (a state-listed threatened species) and to provide habitat for Indiana bat (a federally and state-listed endangered species) and other wildlife species. The VTF&W easements allow “non-mechanized, dispersed, outdoor recreation” as long as it is consistent with the purposes of the grant.

In all, Jim’s team has identified a total of 24 species of herptiles on TWC lands. Jim focused his talk on several uncommon species on that list, to give a sense of just how ecologically important the Lands of The Watershed Center are, and how the conservation easements help protect these species and all of the wildlife that lives there.

Herptile species identified at the Lands of The Watershed Center

Frogs

American Bullfrog

American Toad

Gray Treefrog

Green Frog

Pickerel Frog

Spring Peeper

Wood Frog

Snakes

Common Gartersnake

DeKay’s Brownsnake

Eastern Milksnake

Eastern Ratsnake

Red-bellied Snake

Smooth Greensnake

Salamanders

Blue-spotted Salamander

Eastern Newt

Eastern Red-backed Salamander

Four-toed Salamander

Jefferson Salamander

Northern Dusky Salamander

Northern Two-lined Salamander

Spotted Salamander

Spring Salamander

Turtles

Painted Turtle

Snapping Turtle

Uncommon Herps on the Land

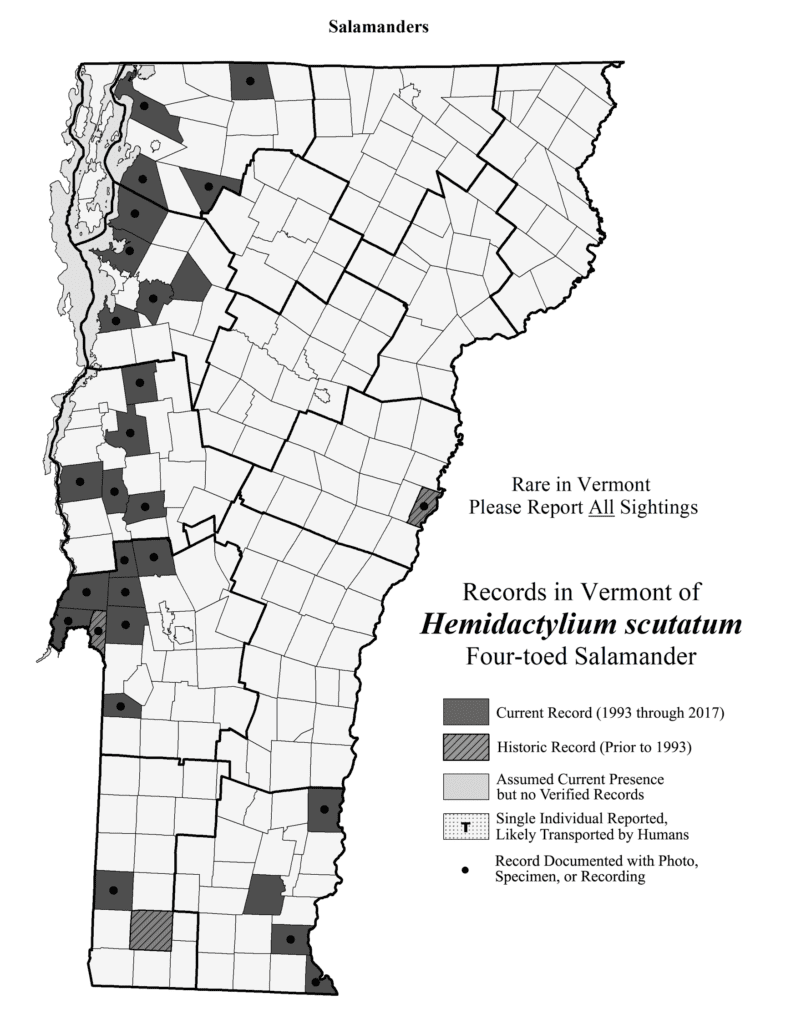

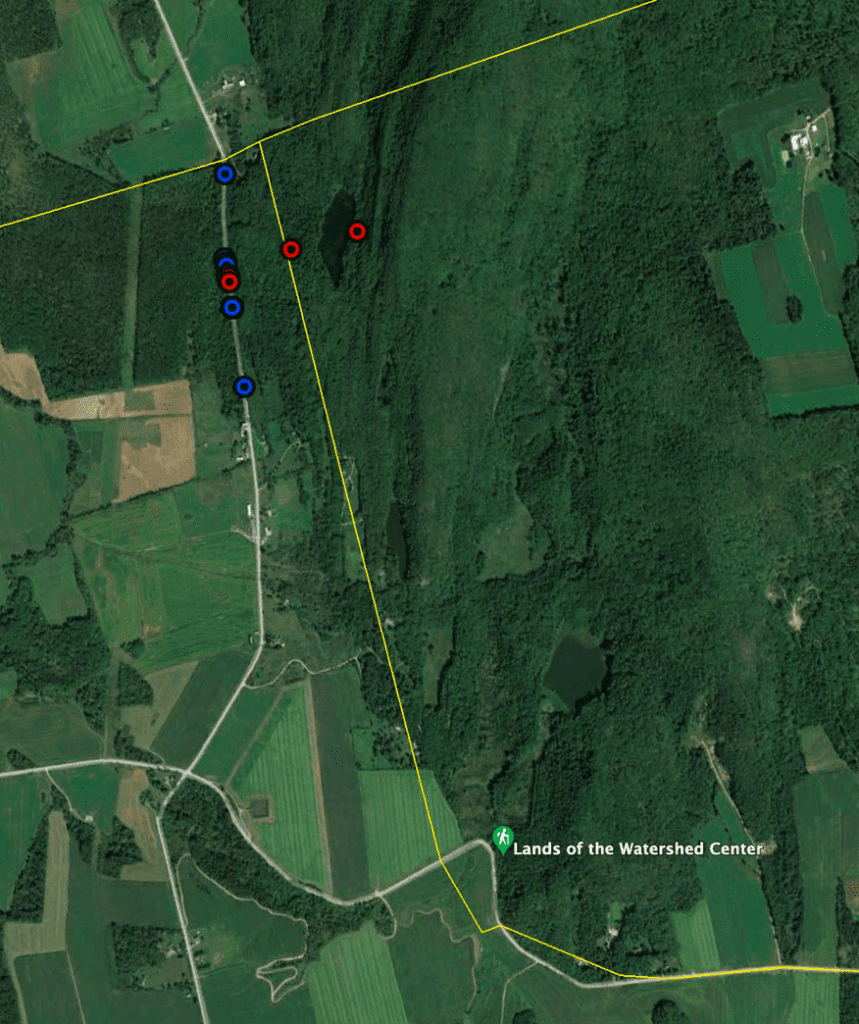

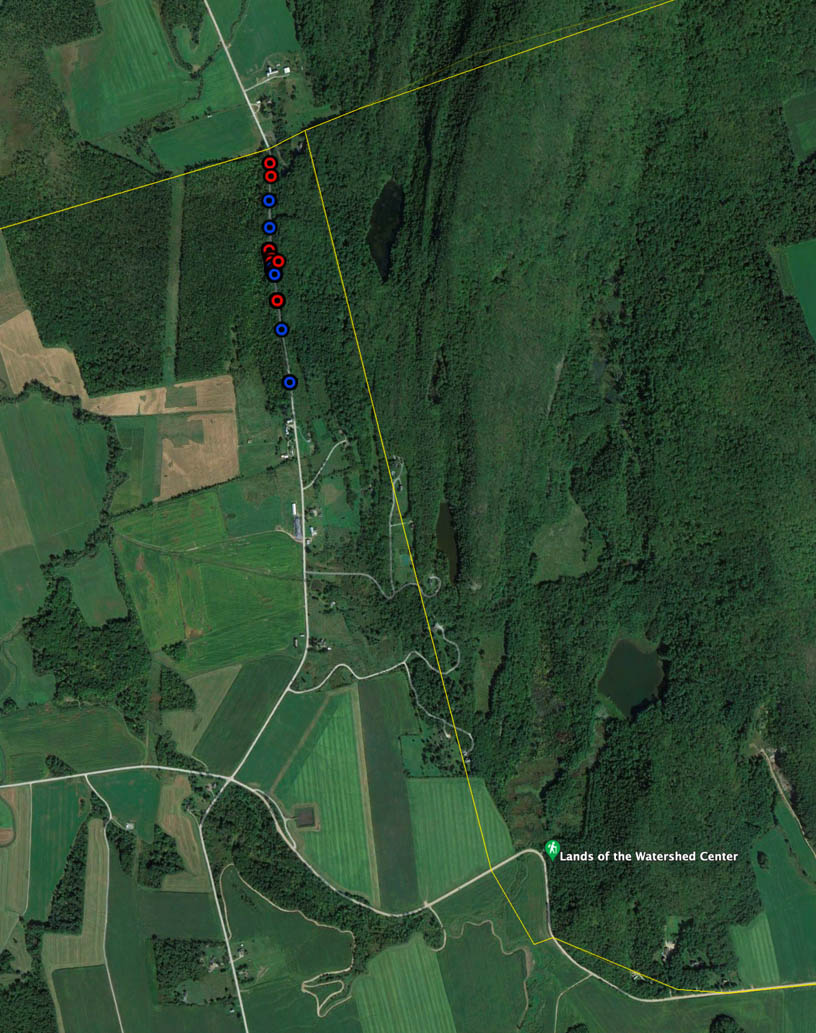

Four-toed Salamander. One of the unusual herp species using TWC lands is the four-toed salamander. Many reports of this species come from the section of North Street that is forested on both sides and that is immediately adjacent to (west of) the Lost Pond parcel. This section of North Street is a major amphibian-crossing area and is one of the two most significant crossings known in Addison and Chittenden counties. Four-toed salamanders have been found at scattered locations in Vermont, mostly in or near the Lake Champlain Basin. They have a State Heritage Rank of S2 (rare), are a species of Special Concern, and a medium-priority species of greatest conservation need (SGCN).

Click to enlarge.

Blue-Spotted Salamander. Significant numbers of blue-spotted salamanders also migrate across North Street into the wooded swamp west of it to breed. Many also spend their summers in the moist soils of the swamp. They return uphill primarily on rainy nights in the fall. Blue-spotteds are largely a Lake Champlain Basin species (in VT) with a few scattered populations elsewhere in the state. They are an S3 (uncommon), special concern, medium-priority species of greatest conservation need (SGCN).

Jefferson Salamander. Jefferson salamanders also move across North Street to breed in the forested swamp to the west of the road. They have also been found breeding in some of the scattered, rocky, vernal and semi-permanent pools on the western slope of the ridge east of North Street. Jefferson salamanders have been found in rocky, upland, deciduous woods in the Lake Champlain Basin and Connecticut River Valley. An S2 (rare) species of special concern, the Jefferson salamander is a high-priority species of greatest conservation need (SGCN).

Threats to Amphibian Populations on TWC Lands

These salamanders need upland deciduous woods with rocky substrate for overwintering, wetlands with woods and coarse woody debris for breeding, and safe access to those wetlands. They face multiple threats, including loss of woody debris on the forest floor, loss of forest canopy cover, loss or alteration of wetland breeding sites, road mortality on warm wet nights, and disease. Hiking trails traversed on dry days should not pose a risk to amphibians, which primarily move on wet nights. Increased traffic on North Street would pose a risk, as would alteration of the wetlands to the west of North Street. Jim noted that there is a parcel that parallels North Street on the west side that would be a valuable conservation addition to the Lands of The Watershed Center.

Uncommon Reptiles on TWC Lands

Smooth Greensnake. Jim’s team (via the Vermont Herp Atlas citizen science monitoring program) has received a handful of smooth greensnake sightings on or near TWC lands in open grassy habitat. This beautiful, solid grass-green snake lives in habitat that offers open, sunny grasses or sedges with rock nearby. The smooth greensnake is found in southern Vermont extending northward in the Lake Champlain Basin and Connecticut River Valley. It is an S3 (uncommon) species, and a medium-priority species of greatest conservation need (SGCN).

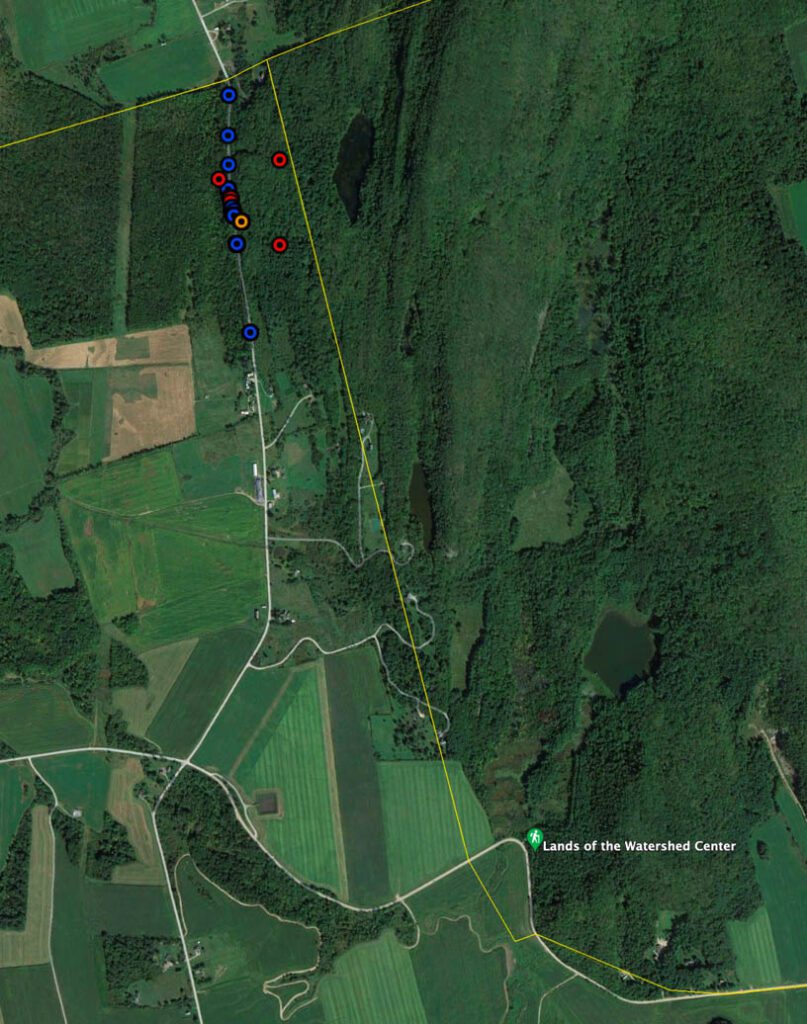

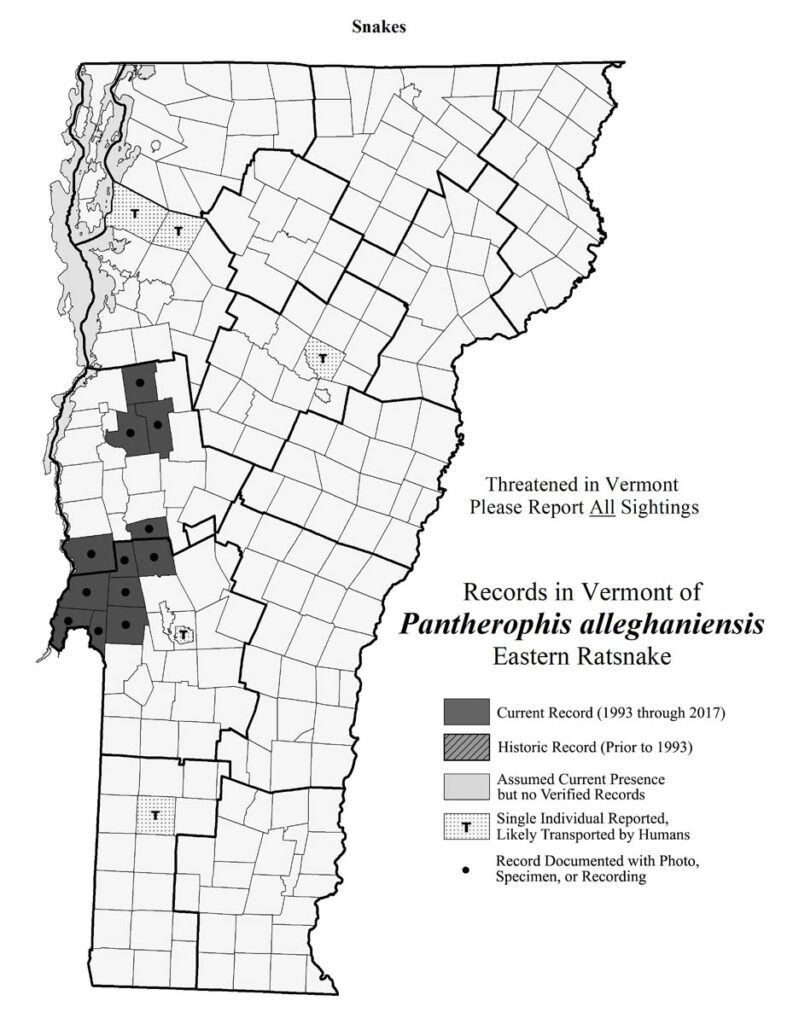

Eastern Ratsnake. Eastern ratsnake has been reported throughout most of TWC lands. This snake prefers forest edge habitat to closed canopy cover but will travel through closed-canopy woods. This species can grow to over 6 feet long, and as an adult is almost solid black, perhaps with a trace of a pattern and white skin showing between their scales. There are twenty different adults known and marked on TWC lands as well as two known denning locations. This is a very small population, as compared with more common species like common gartersnakes, which number in the hundreds on TWC lands.

The eastern ratsnake is an S2 (rare) species that is threatened in Vermont and is a high-priority species of greatest conservation need (SGCN). It is the rarest of the herptiles known on TWC lands. Records have come from hikers, citizen scientists, and radio-tracking. One radio-tracked snake travelled an area of 83 acres on TWC and neighboring lands.

Habitat needs for the eastern ratsnake include edge habitat with wetlands, standing dead trees (hollow is best), rocky talus slopes in which to overwinter, and open and sunny rocky areas. Exposed rock extends their active season and allows them to survive at the northern edge of their range. They are active both day and night depending on temperatures. Removing shade-producing trees on talus slopes is a common conservation practice to improve their habitat.

Herptile Research and Conservation at TWC

Snake Covers and Hotels. To survey and monitor snake populations, Jim and his team set up artificial cover, including slate slabs and snake “hotels,” which provide both heat and protection from predators. At TWC, they’ve set up four slate-cover transects and five snake hotels.

Other herptile research at the Lands of The Watershed Center

Other herpetological research and training activity on TWC lands includes graduate studies on Gray Treefrogs (Matt Gorton, UVM) and the impacts of neonicotinoids on snakes (Rosy Metcalfe, Antioch New England). Jim Andrews also uses TWC lands for field trainings on vernal pools, pond-breeding amphibians, and turtles.

Threats to Reptiles at the Lands of The Watershed Center

Threats include direct persecution (killed by people out of fear or dislike), mowers and agricultural equipment, other wheeled vehicles (cars, four-wheelers, bikes), loss of habitat (for smooth greensnakes, that includes succession of fields to forestland; for eastern ratsnakes, that includes shading over of cliffs and talus slopes), and disease (snake fungal disease). Hiking trails should not be a threat as long as educational signs and other efforts are made to inform hikers on the rarity and value of the snakes. Hikers travel slowly enough to see and avoid snakes. Snakes are vulnerable to wheeled recreation, in which movement is too fast for riders to recognize and safely avoid snakes on trails.

In his closing remarks, Jim noted that humans have taken over management responsibilities of all the land and waters of the planet. If other species are to survive, we must be good landlords and manage those lands in ways that allow other species to co-exist. The conservation easements on the Lands of The Watershed Center help guide and perpetuate such mutually beneficial coexistence.

Thank you, Jim, and thank you to the remarkable community of life on the Lands of The Watershed Center.