Though Vermont is fairly small, as states go, it still encompasses a whole lot more ground than our little organization can know well and effectively respond to. What are the bounds of home? We’ve been pondering that question lately, spurred on by our involvement in recent conversations about the future of Camel’s Hump State Park.

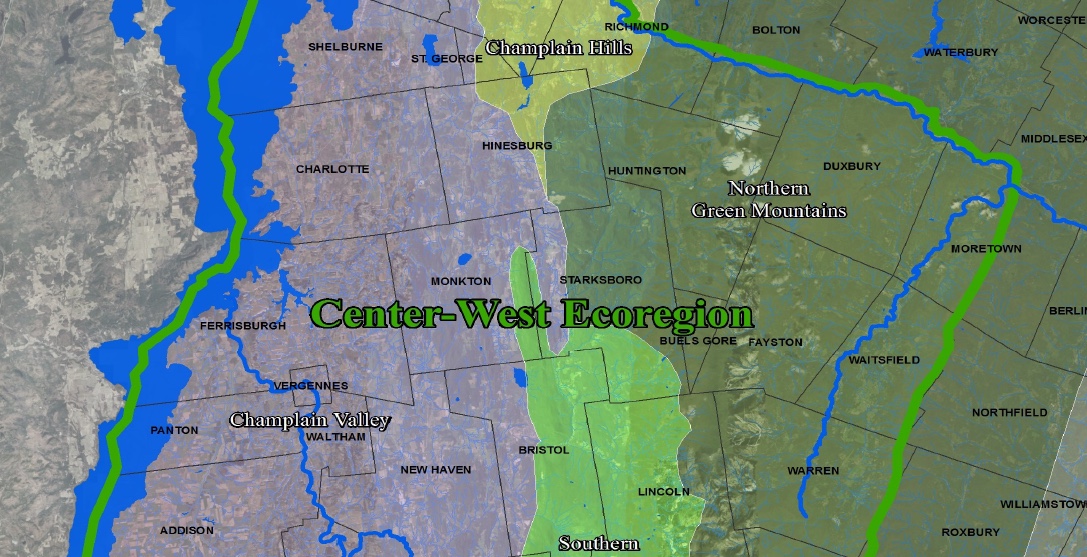

What is emerging as the landscape of home is what we’re calling the Center-West Ecoregion, roughly bounded to the west by Lake Champlain, to the north by the Winooski River (and Route 2), to the east by the Mad River (and Route 100), and to the south by the Middlebury River (and Route 125).

The Center-West Ecoregion includes, in nearly equal portions, lands identified—by such characteristics as climate, geology, topography, and soils—as part of the Northern Green Mountain Biophysical Region to the east and the Champlain Valley Biophysical Region to the west.

We call these home grounds an ecoregion rather than bioregion to include people in the mix of considerations (“Eco” comes from the Greek “oikos,” meaning household.) This ecoregion is where we work and play, where we ski, paddle, hike, pay taxes, raise children, and purchase the things we need to live. For VFF, the Center-West Ecoregion is where we focus our outreach to forest landowners—it’s our stomping grounds.

“All sustainability is local.” William McDonough made this point in his brilliant book entitled Remaking the Way We Make Things. McDonough went on to explain the importance of cultivating an economy that supports a triple top line of healthy ecology, economy, and community. No small task in a world where externalized costs are the norm rather than the exception.

A few ancient examples of McDonough’s local, triple-top-line approach can still be found. In their essay “Sacred Groves” and Ecology: Ritual and Science, FrédériqueApffel-Marglin and Pramod Parajuli highlight the network of sacred groves that once covered the Indian subcontinent. Sir Dietrich Brandis, the first inspector general of forests in colonial India, urged a system of forest reserves modelled upon it. Unfortunately, the British system of forest management failed to heed his advice and the destruction of the groves accelerated with only a handful of notable exceptions.

In those places where the sacred groves were saved, according to Apffel-Marglin and Parajuli, there existed an “ecological ethnicity” that developed “a certain respectful use of the bounty of nature and, consequently, a commitment to create and preserve a technology and conservation system, that interact with the place and its non-human collectivity in an ecologically sustainable manner.”

How can we cultivate this ecological ethnicity—this commitment to conserving the health and vitality of our home place? In many ways VFF’s Organic Forest Ecosystem Conservation Checklist is one step in following their lead. The checklist outlines a sustainable approach to northern hardwood forest conservation that seeks to protect forest health first. It calls for changing our technology by replacing skidders with forwarders and by replacing skid trails with forwarding paths (i.e. lines of grace). This emphasis is key since the eastern side of the forested place we call home is mountainous, fragile, and well-watered. This area requires that we pay special attention to the modes by which forest products are harvested and access trails are constructed.

When we entered into the conversation about management planning for Camel’s Hump State Park—in particular looking at the question of logging within the park—we saw that it made the most sense to consider Camel’s Hump within the larger context of our home ecoregion. Once fully forested, our ecoregion now includes a mosaic of cleared lands, intensively managed forests, forests tended with light-on-the-land forestry practices, and wild forest reserves. Within this ecoregion are areas of public land and private land, as well as interests that can be thought of as a commons, like water, air, and wildlife. Is our current relationship with these lands improving the health and resilience of the ecoregion as a whole?

In his book, Practice of the Wild, Gary Snyder encourages us to find a place, call it home, care for it, and hope that others are doing the same elsewhere. That’s what Vermont Family Forests aims to do here in Vermont’s Center-West Ecoregion.